A D D E N D U M

From States' Rights: The Law Of The Land

By Charles J. Bloch

Originally published in 1958

by The Harrison Company, Atlanta, Georgia

(Copyright expired)

N THE WEEKS just prior to the publication of this work, the nation has been in turmoil because of developments in the State of Arkansas. The Governor of Arkansas "called out" the National Guard of the state after a federal court decree ordering segregation in certain schools to cease. Did he have a legal right so to do?

N THE WEEKS just prior to the publication of this work, the nation has been in turmoil because of developments in the State of Arkansas. The Governor of Arkansas "called out" the National Guard of the state after a federal court decree ordering segregation in certain schools to cease. Did he have a legal right so to do?

In Moyer v. Peabody, 212 U.S. 78, 29 S. Ct. 235, 53 L. Ed. 410, (1908), in an opinion written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, it was held that the declaration of the governor of a state that a state of insurrection exists was conclusive, and that where the constitution and laws of a state gave the governor power to suppress insurrection by the National Guard, as in Colorado, he might also seize and imprison those resisting, he being the final judge of the necessity for such action. The Court said: "So long as such arrests are made in good faith and in the honest belief that they are needed in order to head the insurrection off, the Governor is the final judge and cannot be subjected to an action after he is out of office on the ground that he had not reasonable ground for his belief." (Op. cit. p. 85.)

A quarter of a century later, there was decided Sterling, Governor of Texas, et al. v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378, 53 S. Ct. 190, 77 L. Ed. 375. A District Court, composed of three Judges, Hutcheson, Grubb and Bryant, had granted an interlocutory injunction restraining the Governor of Texas and certain officers of the Texas National Guard from enforcing military and executive orders regulating or restricting the production of oil from complainants' wells and from interfering in any manner with the lawful production of oil from their property.

The complainants, as owners of interests in oil and gas leaseholds had originally brought the suit, on October 13, 1931, against members of the Railroad Commission of Texas, the Attorney General of the state, a Brigadier General of the Texas National Guard and others, to restrain the enforcement of orders of the commission limiting the production of oil. The orders were alleged to be arbitrary and illegal. The District Judge set the application for preliminary injunction for hearing on October 28, 1931, before a specially constituted court of three judges. Meanwhile, he issued a temporary restraining order restraining the defendants from limiting complainants' production below 5,000 barrels per well. The defendants who were members of the Railroad Commission accordingly ceased their attempt to enforce the challenged orders. A couple of months before, Governor Sterling had issued a proclamation stating that certain counties (in which complainants' properties were located) were in "a state of insurrection, riot, tumult and a breach of the peace," and declaring "martial law" in that territory. The Governor directed Brigadier General Wolters to assume supreme command of the situation and to take such steps as he might deem necessary in order "to enforce and uphold the majesty of the law." From that time on, General Wolters acted as "commanding officer of said military district."

When the District Court issued its temporary restraining order the Governor ordered General Wolters to limit the production of oil within the limits fixed in the Commission's order, and subsequently reduced that quantity.

Subsequently, the Governor and the Adjutant-General were by amendment made parties defendant to the suit. In the amended bill it was alleged that the orders limiting production were without justification in law or in fact, were arbitrary and capricious, and repugnant to the State and Federal Constitutions. It was alleged that there had been no request by the civil authorities for the use of military forces; that all courts in said area were "open and transacting their ordinary business"; that there were "no armed bodies of civilians in said area," nor "any bodies of men threatening bloodshed, violence or destruction," but that, on the contrary, "the citizens in said community are in a quiet, peaceable condition and amenable and obedient to any process which might be served upon them." The Governor, and the military officers answered, setting forth the executive proclamation and orders, and the declaration of martial law, and asserting the validity of the acts assailed.

The District Court received evidence submitted by both parties, and found the facts to be substantially as alleged in the amended bill. Having thus found the facts, the District Court, maintaining its jurisdiction, examined the law to determine whether it conferred upon the governor the power he had assumed to exercise, and decided that the Governor and the military officers without warrant of law had been depriving the complainants of their undoubted right to operate their own properties in a prudent and reasonable way, in accordance with the laws of the state. Appealing from a final judgment so holding, the governor contended (1) that he had the power to declare martial law; (2) that courts may not review the sufficiency of facts upon which martial law is declared; (3) that courts may not control by injunction the means of enforcing martial law.

Rejecting these contentions, the Court in an opinion written by Chief Justice Hughes, unanimously affirmed the judgment of the District Court.

The Court used language which directly affects the Arkansas situation.

"By virtue of his duty to 'cause the laws to be faithfully executed,' the executive is appropriately vested with the discretion to determine whether an exigency requiring military aid for that purpose has arisen. His decision to that effect is conclusive." So said the Chief Justice. He then proceeded:

That construction, this Court has said, in speaking of the power constitutionally conferred by the Congress upon the President to call the militia into active service, 'necessarily results from the nature of the power itself, and from the manifest object contemplated.' The power 'is to be exercised upon sudden emergencies, upon great occasions of state, and under circumstances which may be vital to the existence of the Union.' Martin v. Mott, l2 Wheat. 19, 29, 39, 6 L. Ed. 537. Similar effect, for corresponding reasons, is ascribed to the exercise by the Governor of a state of his discretion in calling out its military forces to suppress insurrection and disorder. Luther v. Borden, 7 How. 1, 45, 12 L. Ed. 581; Moyer v. Peabody, 212 U.S. 78, 83, 29 S. Ct. 235, 236, 53 L. Ed. 410. The nature of the power also necessarily implies that there is a permitted range of honest judgment as to the measures to be taken in meeting force with force, in suppressing violence and restoring order, for, without such liberty to make immediate decisions, the power itself would be useless. Such measures, conceived in good faith, in the face of emergency, and directly related to the quelling of the disorder or the prevention of its continuance, fall within the discretion of the executive in the exercise of his authority to maintain peace.

The Court then discussed Mover v. Peabody, supra, and said that in it, it appeared that the action of the Governor had direct relation to the subduing of the insurrection by the temporary detention of one believed to be a participant, and said that the general language of that opinion must be taken in connection with the point actually decided there.

Then, said the Chief Justice: " It does not follow from the fact that the executive has this range of discretion, deemed to be a necessary incident of his power to suppress disorder, that every sort of action the Governor may take, no matter how unjustified by the exigency or subversive of private right and the jurisdiction of the courts, otherwise available, is conclusively supported by mere executive fiat. The contrary is well established. What are the allowable limits of military discretion, and whether or not they have been overstepped in a particular case, are judicial questions.''

During actual war, in the theater of war, there are occasions in which private property may be taken or destroyed to prevent it from falling into hands of the enemy or may be impressed into the public service. In defending his actions in such cases, the officer may show the necessity, but even in those cases the danger must be immediate and impending or the necessity so urgent that would not admit of delay or resort to civil authority. (Mitchell v. Harmony, 13 How. 115, 134, 14 L. Ed. 75; United States v. Russell, 13 Wall, 623, 628, 20 L. Ed. 474.)

The Court proceeded to test the actions of Governor Sterling by these rules of law.

Of his actions, the Chief Justice said:

In the place of judicial procedure, available in the courts which were open and functioning, he set up his executive commands which brooked neither delay nor appeal. In particular, to the process of the federal court actually and properly engaged in examining and protecting an asserted federal right, the Governor interposed the obstruction of his will, subverting the federal authority. The assertion that such action can be taken as conclusive proof of its own necessity and must be accepted as in itself due process of law has no support in the decisions of this Court. Appellants' contentions find their appropriate answer in what was said by this Court in Re Milligan, 4 Wall. 2, 124, 18 L. Ed. 281, a statement as applicable to the military authority of the state in the case of insurrection as to the military authority of the nation in time of war: 'The proposition is this: That in a time of war the commander of an armed force (if in his opinion the exigencies of the country demand it, and of which he is to judge) has the power, within the lines of his military district, to suspend all civil rights and their remedies, and subject citizens as well as soldiers to the rule of his will; and in the exercise of his lawful authority cannot be restrained except by his superior officer or the President of the United States. If this position is sound to the extent claimed, then when war exists, foreign or domestic, and the country is divided into military departments for mere convenience, the commander of one of them can, if he chooses, within the limits, on the plea of necessity, with the approval of the Executive, substitute military force for and the exclusion of the laws, and punish all persons, as he thinks right and proper, without fixed or certain rules. The statement of this proposition shows its importance; for, if true, republican government is a failure, and there is an end of liberty regulated by law. Martial law, established on such a basis, destroys every guaranty of the Constitution, and effectually renders the 'military independent of and superior to the civil poiver' . . . Civil liberty and this kind of martial law cannot endure together; the antagonism is irreconcilable and, in the conflict, one or the other must perish.' (Last emphasis supplied.)

The case of in Re Milligan from which Chief Justice Hughes was quoting arose out of the arrest of Lamdin P. Milligan, a citizen of the United States and of the State of Indiana, on October 5, 1864, at his home in Indiana by order of Major General Hovey, military commandant of the District of Indiana. It is noteworthy that counsel supporting the right of arrest included "Mr. B. F. Butler" who recently had been General B. F. Butler. The opinion was handed down at the December Term, 1866 of the Supreme Court.

Such was the state of the law of the land when Governor Faubus called out the state militia in Little Bock. Did he have a right to do so? That question could have been completely and fully answered by a court which doubtless would have applied the rules of law laid down in the Colorado case and the Texas case to the facts as they would have appeared in evidence. The Governor did not choose to rely on whatever his legal rights may have been under the actual facts and keep the militia on duty in the service of the state. He withdrew them.

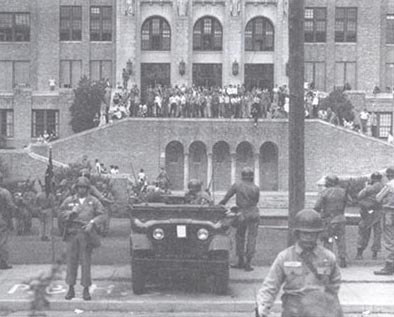

HEREUPON, the President on September 23, 1957, issued a proclamation entitled "Obstruction of Justice in the State of Arkansas" and, based upon it, ordered a detachment of the United States Army into Arkansas to insure the entry of nine negro children into Central High School in Little Rock.

HEREUPON, the President on September 23, 1957, issued a proclamation entitled "Obstruction of Justice in the State of Arkansas" and, based upon it, ordered a detachment of the United States Army into Arkansas to insure the entry of nine negro children into Central High School in Little Rock.

Did he have a legal right to do so?

That question, too, can be determined in the courts of the land.

If our Government is to be one of laws and not of men, it should be so determined.

If the action of the President, doubtless based on advice from his Attorney General, is warranted by present laws, the laws should be changed by Congress, for if present laws warrant such action "republican government is a failure and there is an end of liberty regulated by law."

A year before his Little Rock action, the President has been quoted as saying in a press conference:

Now, I assume that if that marshal is not able to carry it (an order of the Federal Court) out by himself, he has got the right to deputize any number of deputy marshals to help him carry it out. I really don't know what the next step is. I do know this: In a place of general disorder, the federal government is not allowed to go into any state unless called upon by the governor, who must show that the governor is unable with the means at his disposal to preserve order. I believe it is called a Posse Comitatus Act—and I am now going back to my staff school of 1925—of 1882, and that is the thing that keeps the federal government from just going around where he pleases to carry out police duties.

On February 16, 1957, Attorney General Brownell was testifying before the subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary of the United States Senate on certain bills then colloquially known as the "Civil Rights Bills."

His attention was called by Mr. Young of the staff of the full Committee on the Judiciary to a certain section of the United States Code. (42 U.S.C. 1993.)

With respect to that section Mr. Young said: "But they (sic) give permissive power of the President to send the Armed Forces in certain areas for enforcement of court decrees. There has been a deal of worry, General, as you know, as to how far the Federal Government is prepared to go in the enforcement of the court decrees in segregation cases. I would like an expression from you now as to whether this statute is intended at any time or has it been discussed, as being used for enforcement of these decrees?" Attorney General Brownell answered: "I am rather disturbed by you even raising these points, because, as I have said so many times, public statements made by persons who intimate that there is any such thought in the minds of anyone here in Washington to use the militia in these cases does not represent the true state of facts, and I frankly think that the only reason it can be brought into the discussion at all is to confuse the issue. I do not know of any responsible public official of any party of any branch of the Government that has made any statement that would lead to an inference that there is any such thought in the minds of the Congress or the courts or the executive branch of the Government."

Mr. Young persisted, and then asked: "It is possible to do it under that statute, however, is it not, General?" The Attorney General answered: "There are other statutes that would have to be considered in connection with that, and I think you will find the general rule is that the Governor of the state must request the President. We do not want to take away any supplementary aid which the Governor of a state may want." Mr. Young, with patience and fortitude, kept probing, saying then: "I think, General, you have reference to the Governor's right to call for armed help in the case of insurrection. This statute applies to the enforcement of judicial decrees. To go one step further in your platform, you also have a statement as follows: This progress—referring to the progress between the races—must be encouraged—and there they are referring to the court decrees and the work of the court supported in every legal manner by all branches of the Federal Government to the end that the constitutional idea of equality before the law, regardless of race, creed or color will be steadily achieved. Those are mandatory words in the platform—every legal manner must be carried out for the enforcement of those decrees. Would you care to comment on that, sir?"

Mr. Brownell "commented" by answering: "Yes; I think it is rather irresponsible to even bring it into these discussions. No one has had in mind any use of the militia in this situation, and I don't think that there should be any implication that they do."

That did not satisfy Mr. Young. He immediately said: "The point is, General, that I am asking you, sir, the power resides in the President to do this, does it not?" Mr. Brownell answered: "The President is presumed to act in a constitutional way, and I do not think that there is any indication that he is not going to." That did not satisfy Mr. Young either. He asked, "Does he have the power under this statute to do that?'' Before the Attorney General could say "yes" or "no" or anything else, Senator Hennings of Missouri (chairman of the subcommittee) interpolated: "If counsel will yield, is counsel getting at the business that the President of the United States might send troops down to the states of the late Confederacy and enforce these things at the point of a bayonet? Is that what this discussion is leading towards? Is that the purpose of this examination?"

Senator Ervin of North Carolina replied to the Chairman: ". . . if you will pardon me, this statute is not restricted. It exists as to all the states of the Union."

The "debate" continued with Mr. Brownell saying: "I am sure the purpose of the questioning is laudable, but the effect of it is, it seems to me, to confuse two unconnected things. Since there is not the slightest suggestion on the part of any responsible public official of bringing in matters of the militia into the civil rights area, I think it would be quite misleading really to continue with an abstract discussion of a matter which is not pertinent to the main line of our inquiry here this morning."

Shortly after that answer, Senator Ervin said: "But the results of these amendments, if they are adopted, is to extend the power of the President under this statute to call out the Army or the Navy or the militia to enforce judicial decrees in the new cases to be authorized by these amendments so I think it is decidedly germane to the inquiry." After a short discussion between Senators present, Mr. Brownell said: "Mr. Chairman, I believe there is in here an implication that the President of the United States would act recklessly if not unconstitutionally, and I just cannot sit by and have the record contain any such implication of that. I really feel that this has gone far enough. It has no place in these proceedings, and I personally cannot stay here and allow any such implication to be drawn. Now let's have a ruling on that." (Hearings, pages 214-7.)

That is a part of the legislative history which eventuated in the Congress, in the Civil Rights Act of September 9, 1957, specifically repealing section 1993 of Title 42 of the United States Code. That section was thought to be the only law which authorized the use of troops to enforce court decrees in segregation cases.

But, when on September 23, 1957, the President proclaimed, he relied on Title 10 of the United States Code, sections 331, 332, 333 and 334 as revised by the act of August 10, 1956.

The text of the "Notes on the Legal Principles That Have Guided" President Eisenhower in handling the integration situation concluded with a paragraph which throws some light on the question of which of these particular sections the President and his advisers thought applicable.

That paragraph is:

When an obstruction of justice has been interposed or mob violence is permitted to exist so that it is impracticable to enforce the laws, by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings, the obligation of the President under the Constitution and the laws is inescapable. He is obliged to use whatever means may be required by the particular situation.

Was it impracticable to enforce the Little Rock decree by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings?

The ordinary course of judicial proceedings would have required the United States Marshal to enforce the decree. He is the civil officer empowered by law "to execute all lawful writs, process and orders issued under authority of the United States and command all necessary assistance to execute his duties." (Title 28 U.S. Code, Section 547(b).)

Under that statute, a marshal of the United States has the authority to command all necessary assistance to execute a decree of a court.

Under another statute, the military can not act as a posse comitatus. (Title 10 U.S. Code, Section 15.)

The United States Marshal never sought to enforce the decree by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings. It was sought to be done extraordinarly by the invocation of Sections 331, 332, 333 and 334 of Title 10 of the United States Code.

Section 331 is:

Whenever there is an insurrection in any State against its government, the President may, upon the request of its legislature or of its governor if the legislature cannot be convened, call into Federal service such of the militia of the other states, in the number requested by that state, and use such of the armed forces, as he considers necessary to suppress the insurrection.

For the President to act under that section of the statutes, a request from the legislature or the governor would have been a condition precedent. There was no such request. That section is inapplicable.

Section 332 is:

Whenever the President considers that unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States, make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States in any state or territory by the ordinary course of judicial proceeds, he may call into Federal service such of the militia of any state, and use such of the armed forces, as he considers necessary to enforce those laws or to suppress the rebellion.

The language of the paragraph from the "Notes on the Legal Principles That Have Guided" President Eisenhower which has been quoted is strikingly similar to the language of Section 332, so he or some of his advisers must have thought that he had a right to proceed under that section, although his chief legal adviser, Attorney General Brownell, could not have thought so for he had reacted against the "implication that the President of the United States would act recklessly if not unconstitutionally" in calling out the Army or the Navy or the militia to enforce judicial decrees.

Regardless of what anyone thought, the test under that section is to be found in the answer to this question: Were the conditions such as to make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States in the State of Arkansas by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings?

To answer that question it is first necessary to answer another: What laws of the United States were impracticable of enforcement?

The answer is that what was sought to be enforced was not a law of the United States but a court decree. However much entitled to respect a decree of a Federal Court may be, it is not a law of the United States.

"The courts have carefully distinguished between the body of delegated powers, the Constitution, which is the 'supreme law of the land,' and the laws of the United States which are the Acts of Congress. New Orleans M&T R. Co. v. Mississippi, 102 U.S. 135, 26 L. Ed. 96; Beck v. Johnson, 169 F. 154. Even in the Constitution itself, (Article III) this distinction is made: 'Section 2. The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made or which shall be made, under their authority . . .' And again in Article VI of the Constitution: 'This Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof . . .'" United States v. Cooper Corporation et al., 31 Fed. Supp. 848, 851.

"It is settled law . . . that cases arising under the laws of the United States are such as grow out of legislation of Congress, . . ."

So said the Supreme Court of the United States in 1880 in Railroad Company v. Mississippi, supra, at pages 140-1.

Even had it been sought to enforce a law of the United States, as distinguished from a judicial decree, the impracticability of enforcement by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings did not appear.

Section 333 provides:

The President, by using the militia or the armed forces, or both, or by any other means, shall take such measures as he considers necessary to suppress, in a State, any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combinations, or conspiracy, if it—(1) So hinders the execution of the laws of that State, and of the United States within the State, that any part or class of its people is deprived of a right, privilege, immunity, or protection named in the Constitution and secured by law, and the constituted authorities of that State are unable, fail or refuse to protect that right, privilege, or immunity, or to give that protection, or (2) opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States, or impedes the course of justice under those laws.

For the President to have had any power under that section to use the armed forces it must have appeared that an insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination or conspiracy hinders, opposes or obstructs the execution of laws. Under the first division of the section the hindrance must have affected the execution of the laws, not only of the United States, but those of the state. Under the second division, the opposition or obstruction must so affect the execution of the laws of the United States as to impede the course of justice under those laws. A Judicial degree (or fiat) in a particular case is not a law of the United States.

Under our system of Constitutional Government, the military is not independent of and superior to the civil power. On the contrary, the civil authority is superior to the military. Officers of the court, United States Marshals and their deputies, under the law of the land, enforce court decrees and judgments. For one man, though he be a judge, to have the right to issue a decree, and another man, though he be President or Attorney General, to have the right to denominate that decree a law of the United States and call out the army to enforce it would "destroy every guaranty of the Constitution and subordinate liberty under a Constitution to the whims of whatever men might happen to hold high executive and judicial offices at a particular time."

The Congress of the United States, representatives of the people of the United States, unmistakably declared its intent when in the Civil Rights Act of September 9, 1957, it repealed Title 42, Section 1993 of the United States Code. That section was the only section in all of the statutes of the United States which authorized the use of troops to enforce court decrees. Its repeal was unanimous. Other sections of the Statutes have now been perverted for a purpose never intended for them by the Congress. The Congress of the United States, if Constitutional Government is to survive, must act, and act promptly, and say again that in the United States of America troops shall not enforce judicial decrees.

The events of each day which dawns demonstrate to the people of the United States—of the North, South, East and West, that our government will survive only if the Congress enacts legislation to preserve it, restricting the actions of the courts with respect to the Fourteenth Amendment, and revitalizing the corner stone of the Republic, the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States: The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

That this constitutional doctrine of States' Rights is the cornerstone of the Republic was never more graphically demonstrated than by the following language of Justice Harlan, the elder, fifty years ago:

"The preservation of the dignity and sovereignty of the States, within the limits of their constitutional powers, is of the last importance, and vital to the preservation of our system of government. The courts should not permit themselves to be driven by the hardships, real or supposed, of particular cases to accomplish results, even if they be just results, in a mode forbidden by the fundamental law. The country should never be allowed to think that the Constitution can, in any case, be evaded or amended by mere judicial interpretation, or that its behests may be nullified by an ingenious construction of its provisions." Ex Parte Young, 209 U.S. 123, at page 182-3, 28 S. Ct. 441, 52 L. Ed. 714.

# # #

|

The Honorable Mr. Bloch (1893-1974) of Macon, Georgia was one of the most distinguished attorneys in the history of that State. He served as a member of the State House of Representatives, was twice a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, and twice a Presidential Elector for Georgia. He served as president of the Georgia State Bar in 1945, as chairman of the State Judicial Council from its creation in 1946 until 1957, and was a member of the Board of Regents of the University of Georgia. He also served as chairman of the Rules committee for the State Supreme Court. Among the honors he received was the Distinguished Service Scroll Award from the University of Georgia Law School. He was for several years personal advisor to U.S. Senator Richard B. Russell. Mr. Bloch's book States' Rights: The Law Of The Land is considered a classic treatise on the jurisprudence that has evolved under the Fourteenth Amendment, and the threat this presents to our heritage of liberty under law.

|

|

INCE the Federal Government is a parchment created by a written

instrument, which we know as the

Constitution, all officers of that Government, including

the President, must look to that parchment for every power that they exercise, whether in

Washington or in Little Rock. That is true, not only of the President, but of the Congress

and of the Federal Courts.

INCE the Federal Government is a parchment created by a written

instrument, which we know as the

Constitution, all officers of that Government, including

the President, must look to that parchment for every power that they exercise, whether in

Washington or in Little Rock. That is true, not only of the President, but of the Congress

and of the Federal Courts.

BVIOUSLY, there has been no invasion or threatened invasion of

Arkansas, hence the

President had no authority to send federal troops into Arkansas, except upon the

application of the Legislature of Arkansas for the purpose of putting down domestic

violence. The Legislature of Arkansas did not ask for federal troops and since there is no

reason why it could not be convened, the Governor of Arkansas has no authority to call on

the President to send federal troops. If the Governor of Arkansas had such authority he has

not exercised it. Therefore, the President had no authority to send federal troops into

Arkansas under any fair construction of Section 4 of Article IV or of any other provision

of the Constitution.

BVIOUSLY, there has been no invasion or threatened invasion of

Arkansas, hence the

President had no authority to send federal troops into Arkansas, except upon the

application of the Legislature of Arkansas for the purpose of putting down domestic

violence. The Legislature of Arkansas did not ask for federal troops and since there is no

reason why it could not be convened, the Governor of Arkansas has no authority to call on

the President to send federal troops. If the Governor of Arkansas had such authority he has

not exercised it. Therefore, the President had no authority to send federal troops into

Arkansas under any fair construction of Section 4 of Article IV or of any other provision

of the Constitution.

O FEDERAL

or state court of record in America has ever held that a decision of the Supreme

Court of the United States or that of any other federal court is "the law of the land" or

"the Law of the Union." Such decision is never anything more than the law of the case

actually decided by the court and binding only upon the parties to that case and on no

others. As was said by Charles Warren, in his History of the Supreme Court, page 748,

Volume 2:

O FEDERAL

or state court of record in America has ever held that a decision of the Supreme

Court of the United States or that of any other federal court is "the law of the land" or

"the Law of the Union." Such decision is never anything more than the law of the case

actually decided by the court and binding only upon the parties to that case and on no

others. As was said by Charles Warren, in his History of the Supreme Court, page 748,

Volume 2:

T IS contended by some that the 14th

Amendment is involved and that such Amendment

constitutes a "law of the Union" authorizing the use of state troops by the President. If

we concede that the 14th Amendment was legally adopted it provides how it is to be

implemented and enforced. That was not left to chance, caprice—or to Warren. It says in

its last clause that only the Congress has the power to implement or enforce it. If one

line of the Amendment is legal, the last line is legal. If that Amendment confers power on

the Congress to legislate with respect to segregated schools (which need not be discussed

here,) the Congress has passed no law since its adoption relating to segregated schools in

Arkansas or in any other State, except to establish segregated schools in the District of

Columbia and to sanction them in laws relating to the distribution of surplus commodities

in the schools of the states.

T IS contended by some that the 14th

Amendment is involved and that such Amendment

constitutes a "law of the Union" authorizing the use of state troops by the President. If

we concede that the 14th Amendment was legally adopted it provides how it is to be

implemented and enforced. That was not left to chance, caprice—or to Warren. It says in

its last clause that only the Congress has the power to implement or enforce it. If one

line of the Amendment is legal, the last line is legal. If that Amendment confers power on

the Congress to legislate with respect to segregated schools (which need not be discussed

here,) the Congress has passed no law since its adoption relating to segregated schools in

Arkansas or in any other State, except to establish segregated schools in the District of

Columbia and to sanction them in laws relating to the distribution of surplus commodities

in the schools of the states.

HERE IS no "law of the Union" on which the President's order may

legally rest. Since the President had no "law of the Union" to enforce in Little Rock he had

no authority to federalize Arkansas troops.

HERE IS no "law of the Union" on which the President's order may

legally rest. Since the President had no "law of the Union" to enforce in Little Rock he had

no authority to federalize Arkansas troops.